| | |

The statue of Captain James Cook in Whitby

The Journal of The Harrison Butler Association

Editor : Martin Hansen

Proof Reading : Dr Helen Jones

Far East Correspondent : Dr Stephen Davies

Australian Correspondent : David Stamp

Netherlands Correspondent : Michiel Scholtes

Baltic Correspondent : Myriam Spicka

UK Correspondent for The Solent : Robert Griffiths

UK Correspondent for Dartmouth : Allen Clarke

Contributions for the Journal are most welcome be they

fully formed articles, rough notes or snippets of News.

If you feel you would like to contribute on a regular basis,

applications to join our growing network

of correspondents are also invited.

Whitby is an English East Coast seaside port, with an illustrious maritime history, that has successfully reinvented itself as an interesting and quirky place to visit. Its nautical heritage revolves around the fact that one of England's finest naval commanders, Captain Cook, was trained there, and the boats he commanded, Endeavour, Resolution and Discovery, were Whitby built. The reinvention revolves around the fiction that Count Dracula came ashore here, Whitby thus embracing Goth culture, aided by the blackness of the jewellry on sale in many shops, made from the locally sourced semi-precious stone, jet.

The Hansen family spent a week holidaying here last October and greatly enjoyed the Captain Cook Memorial Museum. In the evenings, the baby asleep, I read my way through John Leather's book on the artist and boat designer, Albert Strange. Harrison Butler and he clearly had similar ideas about making boating for pleasure accessible to the common man. To my surprise, I read that Albert Strange had been Headmaster at The Scarborough School of Art, and had been buried near by. Scarborough is a short drive from Whitby and so we went to spend a day there, and visited his grave. The holiday inspired me to join the Albert Strange Association, and to start finding out more about his art and the beautiful boats he designed. It is with pleasure that I have added seventeen Albert Strange designed boats, mostly those still sailing, as invited friends. Getting to know them is rewarding as it places Harrison Butler's work in a broader context.

• Ariel • Charm • Charm II • Charmina • Cherub II • Emerald • Galatea • Imogen (ex Imogen II) • Leona (ex Lalage) Nirvana Of Arklow • Ortegal • Redwing (ex Cherub III) • Sea Harmony • Sheila • Shulah (ex Norma) • Tally Ho (ex Alciope, Betty, Escape) • Venture •

.png)

A Photograph of the staff at Scarborough Art College,

with Albert Strange as Headmaster (c1900)

!•¡•! The first Meet of the year has been announced; 21st and 22nd May 2016. It's on the Isle of Wight, in Bembridge Harbour. Interested sailors to email Richard Farmer.

!•¡•! Boats sold recently: Kelana, and Zoraida. Pre-season bargain : Spindle, down from £15,000 to £5,000 but with a bow not HB designed. For the real deal, in good condition, try Omega of Broom, £15,000.

!•¡•! A new website feature uses Google Maps to display members home ports. It's a visual means to see members boats near your current location. The Yearbook, obtained by becoming a member, contains follow on contact details.

!•¡•! The 2016 AGM tackled, with good humour, a packed agenda. Amendments were made to the Constitution, the new posts of Press officer and Independent Examiner of Accounts created, and thanks expressed to those responsible for the Yearbook, Website, and Social Calendar. Since the last AGM, Harrison Butler's book has been republished and his designs digitised. A large part of the meeting centred of how best to proceed with Grants To Support Boatbuilding Skills, with many thoughtful points made. Members have since received Minutes, updated Constitution, and a covering letter from the Chairman.

Discussions in full flow at the February 2016 AGM

Photograph by Elspeth Macfarlane

Seasalter's Unintended Sea Trial

Jay Lawry

Seasalter's much vaunted departure for places East and certainly South began in a blustery North Easterly in the evening of Thursday 18th February 2016 with the intention of sailing the 250 miles South to the regional city of Tauranga. With crew Fabian Perez Bemporat of Argentina and Liam Prendergast of Dunedin we motored out of our home port in the Bay of Islands toward Russell - reputedly the first capital of New Zealand. In the lee of the high land, we hoisted a double reefed mainsail and little staysail and peeled off to round the headland and the treacherous Tapeka Point. On a close reach into large head seas, we passed Roberton, Motueka and Urupukapuka Islands, inside Whale Rock and off to Cape Brett. Just to give the crew a thrill I sailed between the high Cape light and Piercy Island less than a half mile offshore, before bearing away for the long slide southwards towards Great Barrier Island.

Getting everything sorted and stored had been manic. I'd committed to getting away before February's end but not on a Friday; I've had problems with Friday departures in the past and for such a big journey definitely wanted all Luck Gods onside !

Ahead of departure, winds had been strong, 35 to 40 knots, but favourable - mostly from the North East. It seemed opportune to take advantage. So in 30+ knots we scooted off on our first full-on test of sailing this new, old beauty. Liam suffered from seasickness that night but Fabian, an experienced commercial sailor, and I kept him company as we endured showers and boisterous seas in the darkness. Undaunted, Seasalter charged onward, completely unfazed, and the words of previous owners came to me, “If it blows you are safest on Seasalter”.

By dawn we were at the Poor Knight Islands, a marine reserve. The wind moderated so we shook both reefs, unrolled the furled jib, and away we bounded at 5.5 to 6.5 knots with a following sea. We had hand steered all night and although I found her a little hard mouthed she tracked well if left to her own devices. Certainly the relatively fine entry cleaved through any wave that reckoned on our obstruction ! At noon we were up to Hen and Chicks, another group of islands off the coast of Whangarei. At dusk we were sailing between Great and Little Barrier Islands which lie 30 or so miles to the East of Auckland and are high and verdant. The waters teemed with fish and birds hovered and dove everywhere. It was wonderful to be at sea again.

Through the night we passed through the narrow rocky gap of the Mercury Islands and at dawn on the second morning had Mayor Island just ahead. The wind died. We motored the last 40 miles across the Bay of Plenty to arrive at the stunning entrance to Tauranga harbour. We were escorted to a prime berth at the Tauranga Bridge Marina and all headed for the showers and a drink at the local bar. In a few days Customs would clear us out and we'd be on our way to The Horn. All seemed well, but mutiny was afoot. Half an hour before Customs arrived, one of my crew decided not to sail further with me. He subsequently took the rest of the crew with him. At least in this case Bligh kept his ship !

A few days later I had organised another crew. One, the more experienced, was a New Zealander, the other Canadian. Once again I called the Customs and they cleared us out at the top of the tide in the evening of the 6th of March. Keen to be off, oblivious to the fact that the tide was now falling, we grounded on a sandbar in the middle of the harbour. There we sat until dawn the next day; ignominious but not damaging. We left as soon as we floated off and motor sailed out of the harbour heading the 60 miles to East Cape, the Eastern most point of the North Island. Both crew were seasick for the first couple of days, though they did their watches. By dusk of the third day at sea we were leaving East Cape Island astern, heading South East with the thought that it was going to be the last bit of land we would see for a couple of months. Sadly, not. After a further day, radio advice was to seek shelter as quickly as possible. There was a storm approaching from the South with winds in excess of 50 knots. We turned back to the coast and 18 hours later made the small port of Gisbourne. The New Zealander had had enough and jumped ship. The Canadian said that he wasn't willing to sail for The Horn but would help me sail back home.

My dream of many years standing was falling apart. Two years of restoring Seasalter to be the strong vehicle to carry me across Oceans from New Zealand to the Brazilian Olympics, seemingly, for naught. What should I do? I felt like crumpling into a sobbing heap, crying into flat beer as the fizz left my life.

Then it occurred to me: the world is round. I could get to where I wanted to go by heading in the opposite direction ! And so I accepted the Canadian's offer of help to sail back home. Paul and I left Gisbourne on the morning of the 16th of March, headed around the shallows and rocks of Tuohene Point and shaped a course to the North. With a quartering wind and a single reefed main and staysail we hared off. The Aires wind vane was engaged and kept her on the straight and narrow far better than either of us could. What a joy !

We had a good South Easterly for the next few days, occasionally gusting 45 knots. Seasalter charged back up the coast doing the 320 miles return mostly at speeds of 6.5 to 7.5 knots, although slower when the wind softened in the early hours of each day. A couple of days later with full main, staysail and a half furled jib we surged back into Seasalter's home port in the Bay of Islands. For a sea trial, the unintended circuit was an awesome success. I am very, very impressed with how my boat sails, her motion and her strength. There are things that need to be done; a new companionway hatch is in order and a reduction of the dimensions of the mizzen boom is necessary as it is too heavy for the tiny head of the mizzen mast.

Plan B: Sail for New Caledonia some 1500 miles to the North West and then cross through the Barrier Reef to Cairns in Queensland. There is a very attractive inshore route behind the Barrier Reef that I have sailed many times before and I will follow it up to the Torres Strait and across the Gulf of Carpentaria to Darwin. From there to Mauritius and Durban. I remain convinced that Seasalter is a great ship.

Seasalter, under way after Jay's two year restoration

Frank Hart

(1933-2016)

Richard Hart

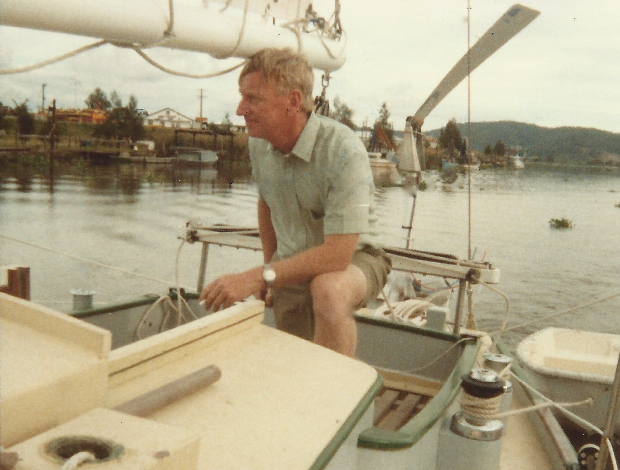

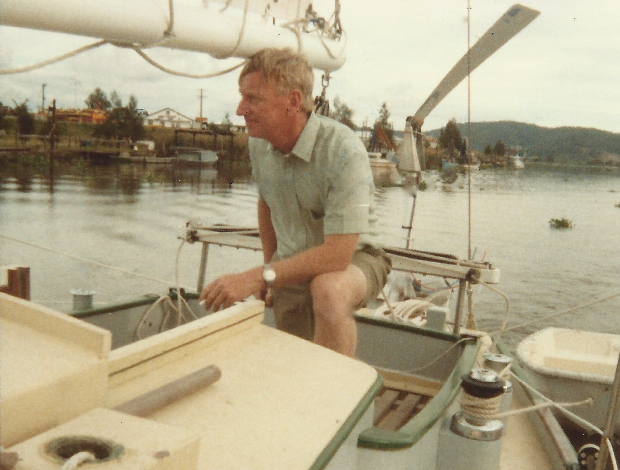

In March 2016 my father, Frank Hart, owner of Isabella, passed away after a brief illness with Pancreatic cancer. He built Isabella thirty-six years ago, planked in celery top pine on spotted gum ribs, and a tallow wood keel. She was sheaved in Dynel. John Hartley then helped Frank fit her out.

Dad sailed Isabella on several extended cruises from her home port of Hastings, Westernport Bay, South Australia. These included voyages to the Whitsunday Islands in Queensland, to the Bay of Islands in New Zealand (his most memorable cruise) and at least once to Hobart in Tasmania. Dad could, and did on occasion, sail Isabella single-handed but more usually had a crew of one or two when making a challenging passage. He particularly liked family to join him for day sailing in the area around a destination.

All of Dad's life revolved around the sea. Born in Liverpool into a family with a long seafaring background, Frank trained at the prestigious Nautical College, Pangbourne, near the Thames. He served in the merchant navy for seventeen years, predominantly with the Shaw, Savill and Albion Line, before becoming Harbour Master at Westernport Bay for twenty years.

My younger brother, Mal, started his boat building apprenticeship at the time of Isabella's launch. His business, Hart Marine, has since become Australia's most successful pilot launch builder. Dad liked the idea of being cremated like a viking, but we didn't want such an end for Isabella. Instead, Mal has undertaken to restore Isabella to her previous immaculate condition, and Frank's ashes will be spread from the stern of the pilot boat at the fairway buoy, at the entrance to Westernport Bay, next month.

Frank enjoyed his membership of the HBA and fondly recalled a Meet at Bucklers Hard that he attended some years ago. He loved the thought that, even though he never planned on sailing through a storm, Isabella was so well designed and built that she would bring him home safely in all weathers. She never let him down.

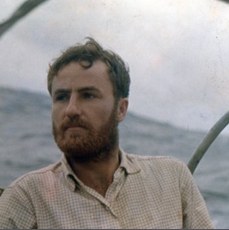

Frank Hart aboard Isabella

Ganga Devi - Part I

~ Preparations ~

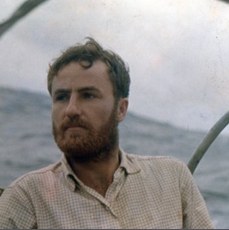

JOC Alexander

Ganga Devi as I first saw her in 1960, at anchor off Castlepeak, Hong Kong

In April 1960 I visited the Royal Hong Kong Yacht Club to look for a boat in which to sail home to England. A constrained budget resulted in consideration being given to a derelict twenty-eight year old steel Harrison Butler designed Cyclone with a chinese family living aboard. She had been shipped to Hong Kong in 1936 for use as a day sailer by the staff of the Holland-America shipping line. My offer of £300 was accepted, leaving me with £200 for renovations and improvements. I renamed her Ganga Devi - “Goddess of the Sea” in Gurkhali - and the Regimental Priest blessed her.

At this time I was a Captain in the Army, in Royal Signals. I had hardly sailed a boat before, although I had completed an assignment to HMS Aurochs, an A class submarine, that included alarming escape training in the water filled tower at Gosport. For my sailing adventure I'd been given a maximum of six months unpaid leave, it being made clear that if I ran into difficulties in Chinese waters, for political reasons, there could be no question of any search or rescue. As Tilman put it, “a kipper must hang by its own tail”.

JOC Alexander, skipper of Ganga Devi, photographed in 1960

at the time of the voyage from Hong Kong to England

In June 1960 Typhoon Mary struck Hong Kong causing severe damage to buildings and loss of life. Ganga Devi, still attached to a massive concrete mooring block was hurled up on rocks and the portside plates caved in below the waterline. After the storm had passed, with the help of fifty Gurkha Engineers, she was refloated. She was leaking seriously and had to be sailed over to Lantau Island, there beached at low tide. In the dark the leaking rivets were replaced with nuts and bolts and tap washers. In the morning she was sailed to the Wing On Shing shipyard for repairs, painting and a large number of modifications to make her more seaworthy; new and stronger fore hatch, higher cockpit sides, washboards across the companionway, and two fifteen gallon water tanks. To my considerable relief the bill was a most reasonable £90. I also procured a bilge pump, gimballed paraffin cooker, compass, storm sails, and an inflatable liferaft. A battered old sextant dated 1913 was found in an antique shop, and an early 3 hp Seagull outboard engine was donated by a well-wisher from the Yacht Club. I was given a few old charts and, importantly, three up to date lifeboat charts that covered the world. I ordered a 2 feet diameter sea anchor with 600 feet of nylon warp. This turned out to be a life-saving purchase.

While the yacht was in the ship yard, I turned my attention to finding a crew. The advertisement in the South China Morning Post said it all....

Girl Friday Wanted For Real Adventure

Hong Kong to England

Share Expenses

Sailing Experience : Useful but Not Essential

There were two replies from apparently keen, extrovert and attractive young ladies. Hopeful of a 24-year-old bachelor's dream come true, I arranged to meet them at the shipyard the day the yacht was relaunched. We met on a Saturday afternoon in July. The first arrived alone and I walked her to the quay where Ganga Devi lay resplendent in new white paint and varnish. Following a brief inspection that revealed no provision for the needs of nature other than squatting on the outboard bracket, she gave me a thumbs down. The second, accompanied by her mother, didn't even bother to get aboard. I can still hear the mother's voice; “Size is everything, darling. It's much too small”.

A view of the Typhoon Shelter at Causeway Bay in Hong Kong.

Dated 1957, a few western yachts are moored to the left.

(From a postcard in the HBA archive)

However, suitable shipmates were found for the first leg of the voyage from Hong Kong to Singapore in the form of Hugh Burt and Rupert French. Hugh was a Radar and Electrical Engineer from the Navy's shore station, HMS Tamar. Available for six months from December, he was an extraordinary tough and resilient character who was to be a tower of strength from the moment he joined. His practical seamanship was invaluable whilst we prepared, not least because he taught me to sail.

I first met Rupert face to face the evening before we sailed ! A young Royal Artillery Officer, the week before he had been racing a Dragon in the harbour owned by the Commander of British Forces in Hong Kong. He'd gybed inadvertently, breaking the mast. The Commander, aware I still lacked one crew member, suggested to him that a quick trip to Singapore would give him necessary experience in challenging conditions and be of great benefit to his character.

Departure was fixed for Thursday 1st December 1960. Hugh, Rupert and I spent our last night partying at the Royal Hong Kong Yacht Club. At 6 am we were up, filling fresh water tanks, and shopping for fresh bread and fruit. It was a cold grey day with a stiff North Easterly. Ganga Devi was secured alongside the Yacht Club pontoon as we said farewell to friends and supporters. I was presented with a plaster figure of Tin Hau, the Chinese sea goddess; a good luck charm. I recall with great clarity the frisson of fear which gripped me as the Editor of the South China Morning Post shook my hand and announced he had come to see us off as he felt sure he would shortly be reporting our deaths.

To be continued...

This recent oil painting by Tracy Butler has been sold

but prints of this attractive image are available to buy for £3

Zyclon, My Boat

Part II

Previously : Part I

Peter Vandenhirtz

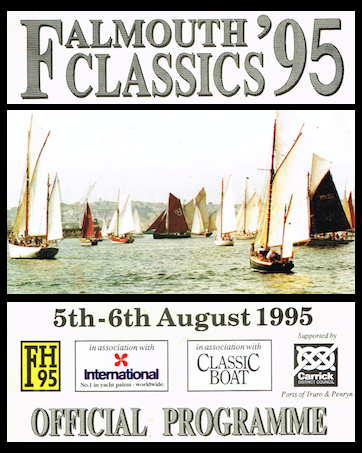

After a Christmas and New Year spent working in Belgium, I returned by train to Falmouth, February 1995. I could now pay Zyclon's marina bills. An acceptable offer came in for my other boat, the Shipman 28. My plan was to sail my Harrison Butler designed Z4 Zyclon back home, to Belgium, where I knew people who would help me restore her. First, I had to get my boat into a fit enough state to cross the English Channel. I scrapped the unreliable old Albin engine, replacing it with a small second hand Arona diesel. I installed new rigging, but decided the existing sails were probably up to the task. To test both man and patched up machine I entered 'us' for the 1995 Falmouth Classics.

I am not a racing enthusiast and was content to potter slowly around the course. Not so the other, bigger boats, which flocked as a mass around me, forcing me to stop admiring the beautiful scenery and take drastic avoiding action. One created a pinch point, forcing me to chose between rocks to starboard and his bow to port. Bang ! As we collided he shouted “Poor Tack” and gesticulated angrily at me. I was hardly moving but I was not, as he seemed to think, stationary. Fortunately, nothing was damaged, except pride.

Come September, I finally sailed Zyclon out of Falmouth, homeward bound. I avoided hugging the coast, prefering to concentrate on some straight forward passage making further out. I had planned a stopover with some friends at Lymington, but the closer we came to the Solent, the more the wind came precisely out of there, piping up to a blustery Force 5. I didn't think it safe to drive my creaking and groaning Zyclon to windward so I sailed on to Brighton, arriving in the middle of the night, after two and a half days at sea. After three days of rest and sorting out leaks, I coastal hopped to Dover in a long day sail. A further day sail saw me arrive in Nieuwpoort, my home port.

A week later Zyclon was in a boatyard in Gent, along with several other wooden boat restoration projects. The chap in charge told me that he could make use of my willing hands to help with the work in the yard, as well as do jobs on my own boat, still afloat until the Spring when she'd be hauled out. I was finally learning some of the basics of wooden boat building other than from books. Before winter set in, I installed a Taylors diesel heater. A week later people were skating around Zyclon, seized in ice, as I worked in her warm interior.

To be continued...

Coffee Break

Martin Hansen

The HBA's Webmaster & Journal Editor

As served up in a small café by Penarth Marina, near Cardiff.

It tasted good too !

HB - An Appreciation

Adlard Coles

Writing in The Yachtsman, Spring 1945

It will come as a great shock to readers to learn of the death of Mr T Harrison Butler, which followed only a week or two after a presentation had been made to him on his retirement from his term of office as President of The Little Ship Club.

I first met Harrison Butler in 1922 when, as an undergraduate, I used to spend the summer vacations on the Hamble River. Although a great many cruising men frequented Bursledon in those days and had moorings in the river, the number of yachts on the Hamble was not so large as in the years immediately before the war, so that everyone knew everybody else. Members of the Royal Cruising Club were prominent in the yachting fraternity centred on the Swanwick Shore, and included Claud Worth, Donald Cree and Harrison Butler, besides many other well known cruising men.

Harrison Butler used to come down with his whole family, and it was always a source of much surprise to me to find how many lived for such long periods in so small a ship. I think it was the fact that he made a home of his boat for himself and his family which influenced the design of the small yachts for which he was so famous. His designs are nearly all family boats; good, sensible little ships in which a man can go down to the sea in comfort with his wife and children and enjoy the life afloat as well as the pleasures of sailing. The plans are thought out so that no space is wasted; there is good headroom to stand under and good height above the settees so that the crew can sit down to a meal in comfort; there is room for hanging and drying clothes, plenty of lockers and always a well thought out galley. It is safe to say that few designers have shown greater ingenuity in getting the maximum amount of comfort into the minimum size of hull. Some yachtsmen, of course, did not like his designs, as they desired faster cruisers or RORC types, but to the majority who wanted wholesome seaboats with good and practical accommodation, the Harrison Butler designs were ideal. He must have designed more of the “tabloid” type and other really small cruising yachts than any other British designer, and possibly more than any other man in the world. His reputation went far beyond the Hamble River or the British Isles, and little ships of his designing have sailed the seven seas. I remember well the first night I was at the club at Åbo, Finland, when I saw a yacht that in some way seemed familiar, lying to her moorings. On enquiring about her I got the answer: “She's a British design by your Mr Harrison Butler. She belongs to a doctor here, and he has sailed her all over the Baltic. She's a strong seaboat”.”

HB, as he was affectionately known by many sailing men, will be particularly remembered as a stout advocate of Admiral Turner's metacentric theory. No subject has been more fiercely debated in yachting circles than this theory, which has many opponents, some of whom attacked it on scientific grounds and others for different reasons, but it may be said that HB, although an ardent advocate of the theory, was never fanatical about it. He believed it to be correct, and when he found that it worked in practice, he supported it. If he had found it to be faulty in any way he would have rejected it, for he was always the first to admit a mistake. This is shown by his attitude towards his own designs; he was his own severest critic and was constantly improving on them.

His research work and the publicity he gave to it has had a profound influence on the design of small yachts. Many newcomers to sailing accept a well-balanced yacht as a commonplace, but before HB directed attention to the matter, small cruising vessels were often hard-mouthed brutes to sail.

Vindilis is the yacht Harrison Butler had built to his own design in 1935.

She is still going strong, frequently seen out and about in The Solent

under the command of the HBA's South Coast Social Secretary, Richard Farmer.

HB was one of the givers of this world. He was always ready to help and was especially kind to young recruits to the game of cruising. Nearly always in the evenings when he was at moorings, there would be a gathering of young people in the cabin of his diminutive yacht, enjoying his hospitality. He was consulted on every imaginable subject connected with small boats and had a great circle of correspondents whom he never failed to answer, replying to each personally on his own typewriter.

His designs were given away, for he would never accept any fee, although he did not refuse donations for any of the charities in which he was interested. At the time of his death he had just received a cheque for £8 for one of his designs which went towards a new electric blower for the organ in the village church. He also refused to accept remuneration for his articles which were so widely read in The Yachtsman. It is with much satisfaction that I am able to place on record another kindly action so typical of the man. In the early part of the war this magazine was very short of articles for publication, a difficulty which was enhanced when everything was lost owing to enemy action in November 1940. It was then that HB hurried to the rescue, writing quickly a series of articles on simple yacht design, which not only bridged the gulf, but proved to be very popular and brought in many new subscribers to the magazine. Later he suggested the designing competitions which have been a feature of The Yachtsman, and he acted as judge in a number of them, giving unsparingly of his time.

He was a big man: big physically and intellectually. Many readers may not know that his work on his hobby of sailing was done after a full day as a busy eye specialist; his was an exacting profession, and it is remarkable that any man could manage a large practice and at the end of the day settle down not only to design yachts but to answer a bulky correspondence and write articles for all the yachting journals. His degrees were MA, DM, FRCS, England. At Oxford he took a First Class Honours degree, and later held a Radcliffe Travelling Fellowship which led to post-graduate work in Berlin, Dresden, Kiel and Vienna. He was ex-president of the Ophthalmological Society of the United Kingdom. At the outbreak of war he returned to the Birmingham Eye Hospital as honorary ophthalmic Surgeon and was doing full time work there until his final illness. In addition to all this, when he was over seventy years of age, he started to renew his acquaintance with Greek; that is the reason why so many Greek words were introduced for the names of his more recent designs. It is no exaggeration to say that whatever HB did he did well; his draughtsmanship was superb, and showed a loving care bestowed on every detail.

During the last year he had been engaged in writing a book on design, based on his articles in The Yachtsman, Yachting Monthly and Yachting World. The publication of the book has been delayed by war-time difficulties, and it is tragic that the proofs should have arrived just too late for him to see them, though happily the whole of the material is available. The book will, in its way, be a classic, and there is some satisfaction in knowing that HB's work will live after him in this permanent form.

With the death of Harrison Butler cruising has lost a great designer of little ships, and yachting a generous friend. His name will long be remembered with those of Dixon Kemp, Albert Strange, Claud Worth and others who contributed in their time so much to the good of amateur cruising.

Thomas Harrison Butler, circa 1920

The photograph has been taken on Day Dawn, his Hamble River house boat

A fall in the value of the Pound against the Euro of around 5%,

means that those boats priced for sale abroad appear to now have higher asking prices.

HB = Harrison Butler Designed

AS = Albert Strange Designed

IF = Invited Friend - The link will give designer detail

Cyclone : HB Cyclone Design : 1941 : Netherlands : £11,500

Iseult : IF : 1909 : Poole, UK : £15,000 Sale Pending

Jane : HB Bogle Design : 1939 : Cornwall, UK : £10,000

Jolanda : HB Omega Design : 1996 : Germany : £27,000

June : HB Z4 : 1939 : Scotland : £7,500 (open to offers)

Kelana : HB Z4 : 1939, Brighton UK : £300

La Bonne : HB Nursery Class : 1919 : Devon, UK : £POA

Leona : AS : 1906 : Yorkshire, UK : £8,500

Mandamus : IF : 1946 : Isle of Wight, UK : £23,000

Omega of Broom : HB Omega Design : 1939 : Tollesbury, UK : £15,000

Saltwind : HB Z4 : 1940 : Spain : £16,000

Sea Harmony : AS : 1937 : Massachusetts, USA : £25,000

Senorita : HB Cyclone II Design : 1934 : New Zealand : £4,000

Spindle : IF : 1983 : Plymouth, UK : £5,000 (open to offers)

Tamaroa : HB Thuella Design : 1973 : £9,000

Tally Ho : AS : 1909 : West Coast, USA : £25,000

Thule : HB Yonne Design : 1934 : Netherlands : £15,000 -£18,000

Witte Walvis : HB Z4 : 1939 : Netherlands : £5,000

Zebedee : HB Z4 : 1938 : Ireland : £4,750

Zephon : HB Z4 : 1950 : Shetland, UK : £4,500

Design Genius Realised

~ Amiri's Bookshelves ~

David Stamp

The HBA's Australian Correspondent

There are many variations on the use of rails to restrain books against the heeling of a boat. Amiri employs removable rails which fit into recesses at their ends. Each of her three shelves has, at one end, an oddly-shaped wooden piece with an open-topped slot, and a blind slot at the other. This arrangement is easy to use, the only requirement being to first engage one end of the rail into the blind slot before dropping the other end into the open-topped slot. It is important that the ends of the rails be rounded, as seen from the opposite side of the saloon, so that as they rotate in dropping into the open slot, they do not become jammed. Both ends are similarly rounded so that the rail can be inserted in any of four ways; right way up, upside down, ends one way or the other.

Having constrained the books athwartships, it is also a good idea to keep them upright, so that they cannot lean over and escape under the rails, so that the titles can be seen (give or take the presence of the rails), and to maintain an orderly appearance. The problem is easily solved by having just the right number of books so that they keep each other vertical, but that requires planning. However, the urge to make adjustable book-ends could not be resisted; I made a device for the small books which is adjustable in steps, and the device for large books is steplessly adjustable. Each device is adjusted by reaching into the space below the bookshelves - there is good access through openings in the vertical panels behind the back-rest settee cushions. The book-end for small books takes some fore-and-aft space, and has two threaded studs projecting downwards through holes in the shelf, so that the book-end can be moved in increments equal to the spacing between the holes. The book-end is held in place by two knurled brass nuts screwed on from below, and cunningly moored to each other with a piece of stainless steel wire so that they can turn but cannot become separated. The larger book-end has to be narrow due to a shortage of space, and slides between guides, with its fixing screw running along a slot in the shelf, and a nut below, fitted with a large wooden hand-grip which secures it in place.

The following nine photographs show further detail. Click on any thumbnail for a magnified view.

.png)

| |

.png)

.png)